The Einheriar paled, their forms thinning to air and light, and they rose from her into the sky.

‘Celemon’

But Susan was left as dross upon the hill, and a voice came to her from the gathering outlines of the stars, ‘It is not yet! It will be! But not yet!’ And the fire died in Susan, and she was alone on the moor, the night wind in her face, joy and anguish in her heart.

But as they crossed the valley, one of the riders dropped behind, and Colin saw that it was Susan. She lost ground, though her speed was no less, and the light that formed her died, and in its place was a smaller, solid figure that halted, forlorn, in the white wake of the riding.

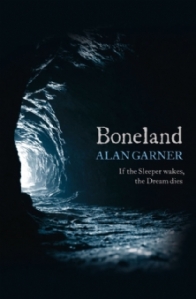

It had never occurred to me that there was meant to be a Weirdstone trilogy, or indeed that there even needed to be. Somehow, the desolation of the final moments of The Moon of Gomrath as Susan is abandoned by the Old Magic had seemed sufficient. Perhaps the novel ended a little abruptly, perhaps I wondered what happened afterwards, but perhaps the same was true of the novels that came after, few of which could be accused of having easy endings. Alan Garner has said that when he begins a novel he knows already what the last line will be; writing the novel is a process of hoping he hits the ending squarely rather than veering off to one side. For the reader, the process is just as hazardous, for an author’s final sentence does not necessarily offer the neat tying-off that readers are taught to look for. Garner’s novels are frequently notable for the uncertainty of their endings. If anything, with the exceptions of the stories forming The Stone Book Quartet, which are tied closely to Garner’s own history, Garner’s endings have become more opaque with each novel. Which brings me to Boneland, Garner’s newest novel, possibly his last, or so the interviews are hinting, and the concluding volume in the newly discovered ‘Weirdstone trilogy’. More tyings-off, it would seem.

The Moon of Gomrath was published in 1963, and here we all are again, over fifty years later. Colin has grown up, acquired a surname and a profession, but along the way he has lost his family, biological and adoptive, not to mention everything else he held most dear. Magic has been replaced by science, in his case astronomy, but also, as so often seems to be the case with scientists, by a fascination with the mechanisms of belief. Oddly, Colin cannot now remember anything before he was thirteen, so those of us familiar with the earlier novels already know more about Colin’s life than he does. On the other hand, Colin remembers many other things; he can, for example, say exactly what he was doing at any particular moment on any given day since he was thirteen. In his dreams, however, he seems to be able to reach deep into the prehistoric past and remember things he cannot possibly have directly experienced and may never have heard about.

And there is one other thing: Colin believes he once had a sister, although everyone else denies this was ever so, and he devotes much of his time to looking for her among the stars, in particular among the Pleiades, Messier object M45. It helps that he works at Jodrell Bank; it is less helpful that he pursues this instead of the project he is supposedly engaged in. As the novel opens, Colin has reached some sort of physical and mental crisis and has sought help, without being clear what kind of help it is that he really needs, other than finding the truth. And that is the short version. The long version? It’s going to take more than one reading to sort that out but I will attempt a first tentative commentary.

The setting returns us to the most familiar element of Garner’s territory, Alderley Edge, the village and the Edge itself, made famous by Garner’s own Weirdstone of Brisingamen. Alderley Edge has changed a good deal since that first novel, being now a playground of the newly wealthy, in particular footballers and their wives, but as far back as Weirdstone, the first hints were already there. Bess and Gowther Mossock were almost the last remnants of a way of life that was fast dying out: the farmhouse, Highmost Redmanhay, was still lit by candles rather than electricity, while farm business was carried out using horse-drawn vehicles, but there were hints throughout the novel, and its sequel, that they were already at a tangent to the contemporary. One remembers the stir that Prince and the cart caused every time the Mossocks went into Alderley and the sharp contrast with Selina Place’s big black car: the Morrigan, source of evil within the novel, naturally embraces the worst of the twentieth century. Similar themes have surfaced in various of Garner’s interviews over the years as he notes the changes to Alderley Edge, in particular the gentrification; the issue is addressed here once again, not least in the reference to ‘the bimbos of Lower Slobovia’ and their tinted-windowed cars.*

Throughout his novels, Garner has firmly delineated his territory: Alderley Edge, Macclesfield Forest, the Peak District, the places he knew as a child, using them as his settings, weaving their names into the story almost as incantations. This surfaces again in Boneland but whereas in Weirdstone and GomrathGarner seemed to be following a ritual: ‘By Seven Firs and Goldenstone they went, to Stormy Point and Saddlebole’ (and a ritual he incidentally reverses for William Buckley’s homecoming in Strandloper), something is different here. Gone are the evocative place names, to be replaced by what at times reads almost like a set of directions from Google Maps. Given that Garner is the most deliberate of writers, this is presumably intentional and significant. Among other things, this internal recitation seems to be one of the ways in which the adult Colin maintains some semblance of structure in his daily life as he cycles round the area. His intimate knowledge of the timings between any two given places, and how to work the gradients to his advantage while cycling indicates how well he knows his patch. At the same time, once plotted on a map, the directions show how circumscribed Colin’s world is. He rarely moves far from the Edge, where he lives in a mountain hut, and then only to go work at Jodrell Bank; even his new therapist conveniently lives within the small area of country in which he apparently feels safe.

One might also read in this shift from places to roads a different kind of relationship with the land, more tenuous somehow, skimming over the surface, as though someone is afraid to make contact with the ground. Even on the Edge itself, although Colin still walks the familiar routes, some places he now avoids while, when visiting the others, he dresses ceremonially, in his academic robes. One thinks perhaps of Cadellin Silverbrow, of Colin filling in for his absence, or maybe Colin protecting himself with the trappings, literally, of knowledge.

The ritualistic yet somehow childlike pleasure of articulating place names and roads reaches its apotheosis in the strange twisting and turning of language, the use of nonsense rhymes and cant that marked Strandloper in particular but which resurfaced too in the historical portions of Thursbitch are here as well, although at times they sit oddly with the contemporary elements of the story – while one might expect it of Colin, who has lived in the area since childhood, is Jodrell Bank really staffed entirely by people who speak English salted with Cheshire dialect?

Garner has always used Cheshire dialect in his novels: he cheerfully admitted that Gowther Mossock was based on his friend, Joshua Birtles, whose speech patterns and vocabulary he transcribed, but as time has gone by the dialect has come more and more to the fore, to the extent that while the volumes of the Stone Book Quartet, originally published in a children’s imprint, are still easily comprehended, Strandloper and parts of Thursbitch, while not actually impenetrable, do not make for easy reading; as a rule, Garner does not include vocabulary lists.

Garner has also always made great play of the connection he perceives between Cheshire dialect and the language used by the Gawain-Poet, writing in North-West Mercian, circa 1400, although so far this has tended to sit in the background.** It’s invariably been represented by a particular phrase, ‘the governor of this gang’. There is a moment in Gawain and the Green Knight when the knight, having entered Arthur’s hall, looks around him and:Þe fyrst word þat he warp, ‘Wher is’, he sayd,’Þe gouernour of þis gyng? That is, who’s in charge around here, his point being that Arthur, whose kingly bearing should be obvious to all is, at that particular point, being anything but kingly as he chases round the hall, playing silly Christmas games. The knight, ‘oueral enker-grene’ as he is, is a far more imposing sight than Arthur. One can read this confrontation in a number of ways, but there is an underlying emphasis on the fact that the Green Knight represents and respects power in a way that Arthur doesn’t; the old challenges the new and underlines his own authority. There is a finely judged contempt in asking for the ‘governor of this gang’. The phrase surfaces in The Stone Book Quartet a number of times, always spoken by members of the Garner family, members of the so-called subordinate classes, underlying a respect for the older ways, and also the perceived authority of the Garners as craftsmen, and is almost always used mockingly of their supposed superiors. And it reappears here as well, when Colin asks a decorator to let him see round a deserted house where the man is working, and the decorator asserts his own authority – ‘I’m the governor of this gang’ said the man, and we’re not on piecework.’ – to give his permission.

At the same time, and pretty much for the first time, Garner goes deeper into the Gawain story. I’ve wondered at times why we’ve not seen a version of Gawain and the Green Knight from Garner; Boneland is perhaps in part an answer, and one in two sections. The simpler, more obvious element lies in an obvious identification of Colin himself with the Green Knight, made explicit in the axe he keeps in his hut, for wood-cutting, and in the fact that his academic hood, worn during his ritual walks, is green. The second element lies in the ‘prehistory’ of this novel, the memories of the Watcher that come to Colin in dreams, centred around a place called Ludscruck, Ludschurch in modern parlance, a place that has been in recent times identified as the Chapel of the Green Knight. (Simon Armitage, who has himself recently produced a wonderful new version of Gawain and the Green Knight, visited Ludschurch for a tv programme about the poem a couple of years back, which showed the extraordinary cleft in the rock which is, according to some, the ‘chapel’. Boneland, though, seems to hint at an idea of the Green Knight as some sort of shaman, reinvented according to the mores of the time. Or rather, Boneland posits the idea of a Watcher, who might be the Green Knight or Cadellin or, indeed, Colin himself. Certainly, this is how Colin sees himself now that Cadellin has vanished; hence, his reluctance to leave the Edge even for a day, so much so that at the beginning of the novel he discharges himself from hospital after some unspecified procedure rather than stay away from the Edge for even one night. Or possibly Colin feels he has to be there in case Susan reappears.

The novel is rich in language, in the past and the present, yet n>ovel by novel I’ve had a sense of the language overtaking the story at times, to the point where what seemed natural if initially slightly unexpected in Weirdstone, Gomrath and the Stone Book Quartet began to seem rather too self-conscious in Strandloper. There Garner was clearly making the point that it is not so much words themselves as the power and intent behind them that matters, thus enabling William Buckley, Cheshire man, to become the shaman of a group of indigenous Australians without necessarily understanding their language. I gather too that his evocation of criminal cant in the transportation sequence runs close to contemporary accounts of its use; his research is always thorough. However, as I’ve already hinted, it seems that the words are overwhelming the story, certainly in the present. One might argue, and I think quite reasonably, that Colin has become a kind of conduit for everything that has gone before, that he is in some way sampling the linguistic past of the Edge and its inhabitants. At the same time, I can’t help wondering if Garner has strayed too far into the self-conscious use of dialect, old song words and so on, as though the story-teller has been replaced by the folklorist and archaeologist.

I’m not sure, either, what I feel about the way in which Garner is reaching deep into past human experience, far beyond and before history. This is, in terms of Garner’s themes, the newest, least familiar material and these are the portions of the novel I really need to think through before I discuss them in more detail. Yet, in a sense allusions to a more personal sense of magic and ritual have always been there, if not so directly articulated – and here I hesitate to use the word ‘shamanic’, although I think this is probably the word Garner himself would use. To begin with, in Weirdstone, it is next to impossible not to read the passage through the Earldelving as anything but some kind of rebirthing of Colin and Susan, fully initiating them into the world of magic, placing them under the aegis of Alderley Edge itself. Here, there are several forms of magic in play. The Morrigan and Cadellin represent a classical approach to magic, for all that the Morrigan is more usually identified with an older Celtic world, but note the use of Latin. The struggle here is between good and evil, a simple dichotomy, no matter the creatures invoked to carry it out. The Old Magic, personified by the likes of Angharad Goldenhand, is not controllable in the same way; it works for its own purposes, which may sometimes coincide with those of the likes of Cadellin.

By contrast, the Old Magic drives Gomrath, a strangely edgy book, choppily plotted at times and shaped by Susan’s seemingly wilful and incomprehensible risk-taking. For a long time I have read this as an attempt to convey the fact that Colin and Susan were now teenagers rather than children, and indeed that Susan was on the threshold of menarche, made explicit in the voice that says, at the end, ‘Leave her! She is but green in power! It is not yet!’ (and indeed my reading is in part confirmed by a comment made by Meg, Colin’s therapist, in Boneland). Elidor in part edges around similar themes, added to which we have Malebron as Fisher King, wounded, trying to maintain the integrity of his kingdom by moving between worlds.

In Red Shift, in the Romano-British portion, Logan, Face and Macey and the other Roman soldiers are holed up on Mow Cop with the girl who is the tribal corn goddess and who, through the ritual grinding of corn, in a place which has significance as part of the grindstone of the world, poisons them. Macey himself is a berserker, who has visions which link him with Thomas Rowley and Tom, his historical counterparts. Ritual plays a significant part throughout the novel, as everyone attempts, one way or another, to keep their daily lives intact.

The repetition of ceremonial performance, allied to the recapitulation of certain events, generation after generation, comes to the fore in The Owl Service, here with the implication that the pattern needs to be broken in order to achieve closure, rather than maintained and thus prolonging the tragedy. Strandloperand Thursbitch both look at the consequences of maintaining ritual which has become emptied of meaning and also, perversely, of the perils of failing to maintain ritual.

In Boneland I think Garner is, among other things, finally addressing the question of where ritual and ceremony come from, what brought them into being, and what is necessary to maintain faith with the original without rendering it meaningless; if you like, how is ritual practice refreshed from one generation to another. At the same time, one can see also that some of Colin’s attempts to devise fresh ritual to maintain himself as a whole and complete being in the 21st century have clearly failed. Travel directions are not the same as the incantatory weight of ‘Seven Firs and Goldenstone and Stormy Point to Saddlebole’. By the end of the story it becomes clear why Colin had eschewed this ritual but equally, that its necessary restoration comes about through renewal rather than through restitution. This in turn is linked to an exploration of the wellsprings from which story is derived.

There are other things going on in Bonelandnot least among them the presence of Bert the unusually conscientious taxi-driver and Meg the not-terribly-professional therapist. Both are marked as being in some way significant by, once again, the strong Cheshire accents. From the beginning Bert reminded me strongly of Gowther Mossock – the speech patterns are very much the same, but Meg’s relationship with Colin, part-mother, part would-be lover, is more complex, though I think she is some kind of analogue for Bess Mossock. As the story unfolds, the reader is obliged to question their corporeality and to wonder whether it is actually wise to assume that any part of this novel is taking place outside Colin’s head or whether, rather, it is an entirely internal struggle to make sense of his past experiences, not least because Meg seems able to so easily glean the information that appears to have eluded Colin, and indeed his doctors and therapists, for so long, not least to confirm that he indeed had a twin sister.

None of this resolves the question of what happened to Susan. Given the circumstances of her disappearance, did she actually vanish into some other universe, as Colin seems to suspect, or did she drown, her body remaining undiscovered, or run away, or was she kidnapped, murdered? Is Colin attempting to conjure her into existence again in some arcane way or is he trying to finally reconcile himself to her loss, and indeed to the loss of childhood, the deaths of his parents and the Mossocks, and indeed Highmost Redmanhey, his home. Colin has for too long been a man cut adrift, floating in time and space; perhaps this novel attempts to ground him, but figuratively rather than literally.

There is of course more, much more, for Garner’s novels are always densely layered, capable of yielding new thoughts and ideas through many, many rereadings. What I find noticeable here, though, is a sense that Garner is drawing on his entire output in a way I’ve not seen him do before. At its crudest, one might play Garner Bingo: I’ve already mentioned the various references to the ‘governor of this gang’, but to take another example, early on, Colin, in some sort of fit, begins to refer to ‘blue silver’, which immediately brings to mind Tom and his historical counterparts in Red Shift, united by their epileptic fits, in which, among other things, they see blue and silver. Indeed, contemporary Tom’s explanation of the speed at which he and Jan are moving in relation to the cars on the M6 is reprised in part by Colin when he entertains Meg the therapist to dinner in his hut, and one might think too of Sal and Ian in Thursbitch, whose dialogue strikingly echoes that of Tom and Jan, as indeed do many of Colin’s conversations with Meg. More subtly, I have the distinct impression that Colin, perhaps mistakenly, identifies Meg with Selina Place: his discovery of her long empty house reminds me strongly of the way in which Errwood Hall flutters in and out of existence. And undoubtedly further readings will produce more resonances. Colin is, for example, much preoccupied with a stone axe he acquires from his project director; one recalls that a stone axe is the linking object in Red Shift, but here it will take on a much deeper significance.

This brings me back to an issue I touched on earlier, the sense of this novel being rather more deliberately self-conscious than its predecessors. On the one hand I find myself wondering whether Garner has all along envisaged his oeuvre as a huge single work; on the other, I wonder if he has quite deliberately attempted to incorporate elements of them into this, his supposedly final novel, or … well, who knows. There is a level on which one doesn’t like to second-guess the intentions of authors but given what I’ve read of Garner’s biography over the years, it’s difficult to avoid recognising things such as descriptions of his own therapeutic processes – and here I think especially of the time surrounding the filming of The Owl Service and the fits of vomiting it provoked in Garner, as well as his accounts of his therapist encouraging him to go to the source of the pain. However, I think it is at its most self-conscious in being the final part of a trilogy rather than a stand-alone novel. I can see why, on one level, it becomes the third part of a trilogy, with the return to Alderley Edge, and to Colin – such a choice brings with it a sense of a certain amount of the work being done for reader and story-teller alike, and one thinks also of the idea of the worm ouroborous, its tail in its mouth, the end at the beginning and so forth, but I wonder too if Garner isn’t, in this way, trying also to undermine the narrative linearity of those early novels, to belatedly shatter them into the fragments of story that his later novels are so often composed of.

In the end, it’s probably far too soon to pass a judgement on this novel. It will take more than one reading to fully digest what’s going on. I haven’t even begun, for example, to unpick the Arthurian references beyond Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, though they are of course there from the beginning, in Weirdstone. For the time being, however, my sense is that this is Garner’s most personal novel and indeed his most complex, a detailed statement of his perception of the world.

‘That’s your modern thought,’ said Colin. ‘We have to make the imaginative leap into the ancient mind and the likelihood of a different world view. I agree that you could argue that for a thing to have a multitude of possible meanings is tantamount to its having no meaning at all. But perhaps the opposite could once have applied. Perhaps a thing that could be thought to have a multitude of meanings, then, gained strength and importance from the ambiguities. We simply don’t know. Nor is there any way of our knowing, whatever “the present” may be; but we must keep our minds open; though, yes, not so open that our brains drop out.’

*I still haven’t forgotten my shock when, the last time I passed through Alderley Edge, some years ago, I found myself confronted by a pub which had been turned into ‘Brisingamens Brasserie’.

** Garner and his friend, Professor Ralph Elliott, have a party piece in which Garner recites the Lord’s Prayer in Cheshire dialect while Elliott simultaneously recites it in Middle English. The divergences are not as many as one might suppose, which is of course Garner’s point.

Off to the Pleiades, kthxbaiI am much, much too close to Susan's story to make any objective judgment, but needless to say, I enjoyed the book. Can't imagine what a non local would make of the language and descriptions. I know these places, it's easy form me, must mean bugger all to someone from London (let alone Sydney or New York or Eccles).

The poem Pearl, I feel, is as much inherent in the work as Gawain (both by the same anonymous poet)… in fact a cursory knowledge of Pearl furnishes one with the answer to many mysteries…I don't want to spoil anyone's research, but I suggest the intrepid reader looks into the authorship question, and the possible identity of the daughter in Pearl – and they'll find one of the main characters by name.The taxi driver and his taxi company's name, and that of its receptionist are all pure Gawain – as is much of the prehistory story – look at the beasts the lone ancient one hunts…Garner is a master.

Maureen, Sue here, we are having a very interesting discussion here- http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2012/aug/31/reading-group-alan-garner-boneland?commentpage=1#end-of-comments